Electromagnetic spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of all possible frequencies of electromagnetic radiation.[1] The "electromagnetic spectrum" of an object is the characteristic distribution of electromagnetic radiation emitted or absorbed by that particular object.

The electromagnetic spectrum extends from low frequencies used for modern radio communication to gamma radiation at the short-wavelength (high-frequency) end, thereby covering wavelengths from thousands of kilometres down to a fraction of the size of an atom. It is for this reason that the electromagnetic spectrum is highly studied for spectroscopic purposes to characterize matter.[2] The limit for long wavelength is the size of the universe itself, while it is thought that the short wavelength limit is in the vicinity of the Planck length,[3] although in principle the spectrum is infinite and continuous.

Contents |

Range of the spectrum

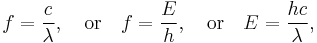

Electromagnetic waves are typically described by any of the following three physical properties: the frequency f, wavelength λ, or photon energy E. Frequencies range from 2.4×1023 Hz (1 GeV gamma rays) down to the local plasma frequency of the ionized interstellar medium (~1 kHz). Wavelength is inversely proportional to the wave frequency,[2] so gamma rays have very short wavelengths that are fractions of the size of atoms, whereas wavelengths can be as long as the universe. Photon energy is directly proportional to the wave frequency, so gamma rays have the highest energy (around a billion electron volts) and radio waves have very low energy (around a femto electron volts). These relations are illustrated by the following equations:

where:

- c = 299,792,458 m/s is the speed of light in vacuum and

- h = 6.62606896(33)×10−34 J s = 4.13566733(10)×10−15 eV s is Planck's constant.[7]

Whenever electromagnetic waves exist in a medium with matter, their wavelength is decreased. Wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation, no matter what medium they are traveling through, are usually quoted in terms of the vacuum wavelength, although this is not always explicitly stated.

Generally, EM radiation is classified by wavelength into radio wave, microwave, infrared, the visible region we perceive as light, ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays. The behavior of EM radiation depends on its wavelength. When EM radiation interacts with single atoms and molecules, its behaviour also depends on the amount of energy per quantum (photon) it carries.

Spectroscopy can detect a much wider region of the EM spectrum than the visible range of 400 nm to 700 nm. A common laboratory spectroscope can detect wavelengths from 2 nm to 2500 nm. Detailed information about the physical properties of objects, gases, or even stars can be obtained from this type of device. Spectroscopes are widely used in astrophysics. For example, many hydrogen atoms emit a radio wave photon that has a wavelength of 21.12 cm. Also, frequencies of 30 Hz and below can be produced by and are important in the study of certain stellar nebulae[8] and frequencies as high as 2.9×1027 Hz have been detected from astrophysical sources.[9]

Rationale

Electromagnetic radiation interacts with matter in different ways in different parts of the spectrum. The types of interaction can be so different that it seems to be justified to refer to different types of radiation. At the same time, there is a continuum containing all these "different kinds" of electromagnetic radiation. Thus we refer to a spectrum, but divide it up based on the different interactions with matter.

| Region of the spectrum | Main interactions with matter |

|---|---|

| Radio | Collective oscillation of charge carriers in bulk material (plasma oscillation). An example would be the oscillation of the electrons in an antenna. |

| Microwave through far infrared | Plasma oscillation, molecular rotation |

| Near infrared | Molecular vibration, plasma oscillation (in metals only) |

| Visible | Molecular electron excitation (including pigment molecules found in the human retina), plasma oscillations (in metals only) |

| Ultraviolet | Excitation of molecular and atomic valence electrons, including ejection of the electrons (photoelectric effect) |

| X-rays | Excitation and ejection of core atomic electrons, Compton scattering (for low atomic numbers) |

| Gamma rays | Energetic ejection of core electrons in heavy elements, Compton scattering (for all atomic numbers), excitation of atomic nuclei, including dissociation of nuclei |

| High-energy gamma rays | Creation of particle-antiparticle pairs. At very high energies a single photon can create a shower of high-energy particles and antiparticles upon interaction with matter. |

Types of radiation

The types of electromagnetic radiation are broadly classified into the following classes:[2]

- Gamma radiation

- X-ray radiation

- Ultraviolet radiation

- Visible radiation

- Infrared radiation

- Microwave radiation

- Radio waves

This classification goes in the increasing order of wavelength, which is characteristic of the type of radiation.[2] While, in general, the classification scheme is accurate, in reality there is often some overlap between neighboring types of electromagnetic energy. For example, SLF radio waves at 60 Hz may be received and studied by astronomers, or may be ducted along wires as electric power, although the latter is, in the strict sense, not electromagnetic radiation at all (see near and far field) The distinction between X-rays and gamma rays is based on sources: gamma rays are the photons generated from nuclear decay or other nuclear and subnuclear/particle process, whereas X-rays are generated by electronic transitions involving highly energetic inner atomic electrons. In general, nuclear transitions are much more energetic than electronic transitions, so gamma-rays are more energetic than X-rays, but exceptions exist. By analogy to electronic transitions, muonic atom transitions are also said to produce X-rays, even though their energy may exceed 6 megaelectronvolts (0.96 pJ),[10] whereas there are many (77 known to be less than 10 keV (1.6 fJ)) low-energy nuclear transitions (e.g., the 7.6 eV (1.22 aJ) nuclear transition of thorium-229), and, despite being one million-fold less energetic than some muonic X-rays, the emitted photons are still called gamma rays due to their nuclear origin.[11]

Also, the region of the spectrum of the particular electromagnetic radiation is reference frame-dependent (on account of the Doppler shift for light), so EM radiation that one observer would say is in one region of the spectrum could appear to an observer moving at a substantial fraction of the speed of light with respect to the first to be in another part of the spectrum. For example, consider the cosmic microwave background. It was produced, when matter and radiation decoupled, by the de-excitation of hydrogen atoms to the ground state. These photons were from Lyman series transitions, putting them in the ultraviolet (UV) part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Now this radiation has undergone enough cosmological red shift to put it into the microwave region of the spectrum for observers moving slowly (compared to the speed of light) with respect to the cosmos. However, for particles moving near the speed of light, this radiation will be blue-shifted in their rest frame. The highest-energy cosmic ray protons are moving such that, in their rest frame, this radiation is blueshifted to high-energy gamma rays, which interact with the proton to produce bound quark-antiquark pairs (pions). This is the source of the GZK limit.

Radio frequency

Radio waves generally are utilized by antennas of appropriate size (according to the principle of resonance), with wavelengths ranging from hundreds of meters to about one millimeter. They are used for transmission of data, via modulation. Television, mobile phones, wireless networking, and amateur radio all use radio waves. The use of the radio spectrum is regulated by many governments through frequency allocation.

Radio waves can be made to carry information by varying a combination of the amplitude, frequency, and phase of the wave within a frequency band. When EM radiation impinges upon a conductor, it couples to the conductor, travels along it, and induces an electric current on the surface of that conductor by exciting the electrons of the conducting material. This effect (the skin effect) is used in antennas.

Microwaves

The super-high frequency (SHF) and extremely high frequency (EHF) of microwaves come after radio waves. Microwaves are waves that are typically short enough to employ tubular metal waveguides of reasonable diameter. Microwave energy is produced with klystron and magnetron tubes, and with solid state diodes such as Gunn and IMPATT devices. Microwaves are absorbed by molecules that have a dipole moment in liquids. In a microwave oven, this effect is used to heat food. Low-intensity microwave radiation is used in Wi-Fi, although this is at intensity levels unable to cause thermal heating.

Volumetric heating, as used by microwave ovens, transfers energy through the material electromagnetically, not as a thermal heat flux. The benefit of this is a more uniform heating and reduced heating time; microwaves can heat material in less than 1% of the time of conventional heating methods.

When active, the average microwave oven is powerful enough to cause interference at close range with poorly shielded electromagnetic fields such as those found in mobile medical devices and cheap consumer electronics.

Terahertz radiation

Terahertz radiation is a region of the spectrum between far infrared and microwaves. Until recently, the range was rarely studied and few sources existed for microwave energy at the high end of the band (sub-millimetre waves or so-called terahertz waves), but applications such as imaging and communications are now appearing. Scientists are also looking to apply terahertz technology in the armed forces, where high-frequency waves might be directed at enemy troops to incapacitate their electronic equipment.[12]

Infrared radiation

The infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum covers the range from roughly 300 GHz (1 mm) to 400 THz (750 nm). It can be divided into three parts:[2]

- Far-infrared, from 300 GHz (1 mm) to 30 THz (10 μm). The lower part of this range may also be called microwaves. This radiation is typically absorbed by so-called rotational modes in gas-phase molecules, by molecular motions in liquids, and by phonons in solids. The water in Earth's atmosphere absorbs so strongly in this range that it renders the atmosphere in effect opaque. However, there are certain wavelength ranges ("windows") within the opaque range that allow partial transmission, and can be used for astronomy. The wavelength range from approximately 200 μm up to a few mm is often referred to as "sub-millimetre" in astronomy, reserving far infrared for wavelengths below 200 μm.

- Mid-infrared, from 30 to 120 THz (10 to 2.5 μm). Hot objects (black-body radiators) can radiate strongly in this range. It is absorbed by molecular vibrations, where the different atoms in a molecule vibrate around their equilibrium positions. This range is sometimes called the fingerprint region, since the mid-infrared absorption spectrum of a compound is very specific for that compound.

- Near-infrared, from 120 to 400 THz (2,500 to 750 nm). Physical processes that are relevant for this range are similar to those for visible light.

Visible radiation (light)

Above infrared in frequency comes visible light. This is the range in which the sun and other stars emit most of their radiation and the spectrum that the human eye is the most sensitive to. Visible light (and near-infrared light) is typically absorbed and emitted by electrons in molecules and atoms that move from one energy level to another. The light we see with our eyes is really a very small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. A rainbow shows the optical (visible) part of the electromagnetic spectrum; infrared (if you could see it) would be located just beyond the red side of the rainbow with ultraviolet appearing just beyond the violet end.

Electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength between 380 nm and 760 nm (790–400 terahertz) is detected by the human eye and perceived as visible light. Other wavelengths, especially near infrared (longer than 760 nm) and ultraviolet (shorter than 380 nm) are also sometimes referred to as light, especially when the visibility to humans is not relevant. White light is a combination of lights of different wavelengths in the visible spectrum. Passing white light through a prism splits it up in to the several colors of light observed in the visible spectrum between 400 nm and 780 nm.

If radiation having a frequency in the visible region of the EM spectrum reflects off an object, say, a bowl of fruit, and then strikes our eyes, this results in our visual perception of the scene. Our brain's visual system processes the multitude of reflected frequencies into different shades and hues, and through this not-entirely-understood psychophysical phenomenon, most people perceive a bowl of fruit.

At most wavelengths, however, the information carried by electromagnetic radiation is not directly detected by human senses. Natural sources produce EM radiation across the spectrum, and our technology can also manipulate a broad range of wavelengths. Optical fiber transmits light that, although not necessarily in the visible part of the spectrum, can carry information. The modulation is similar to that used with radio waves.

Ultraviolet light

Next in frequency comes ultraviolet (UV). The wavelength of UV rays is shorter than the violet end of the visible spectrum but longer than the X-ray.

Being very energetic, UV rays can break chemical bonds making molecules unusually reactive or ionizing them (see photoelectric effect) in general changing their physical behavior. Sunburn, for example, is caused by the disruptive effects of UV radiation on skin cells, which is the main cause of skin cancer. UV rays can irreparably damage the complex DNA molecules in the cells producing thymine dimers making it a very potent mutagen. The sun emits a large amount of UV radiation, which could potentially turn Earth into a barren desert. However, most of it is absorbed by the atmosphere's ozone layer before it reaches the surface.

X-rays

After UV come X-rays, which are also ionizing, but due to their higher energies they can also interact with matter by means of the Compton effect. Hard X-rays have shorter wavelengths than soft X-rays. As they can pass through most substances, X-rays can be used to 'see through' objects, the most notable ones being diagnostic X-ray images in medicine (a process known as radiography), as well as for high-energy physics and astronomy. Neutron stars and accretion disks around black holes emit X-rays, which enable us to study them. X-rays are given off by stars and are strongly emitted by some types of nebulae.

Gamma rays

After hard X-rays come gamma rays, which were discovered by Paul Villard in 1900. These are the most energetic photons, having no defined lower limit to their wavelength. They are useful to astronomers in the study of high-energy objects or regions, and find a use with physicists thanks to their penetrative ability and their production from radioisotopes. Gamma rays are also used for the irradiation of food and seed for sterilization, and in medicine they are used in radiation cancer therapy and some kinds of diagnostic imaging such as PET scans. The wavelength of gamma rays can be measured with high accuracy by means of Compton scattering.

Note that there are no precisely defined boundaries between the bands of the electromagnetic spectrum. Radiation of some types have a mixture of the properties of those in two regions of the spectrum. For example, red light resembles infrared radiation in that it can resonate some chemical bonds.

See also

References

- ^ "Imagine the Universe! Dictionary". http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/dict_ei.html#em_spectrum.

- ^ a b c d e Mehta, Akul. "Introduction to the Electromagnetic Spectrum and Spectroscopy". Pharmaxchange.info. http://pharmaxchange.info/press/2011/08/introduction-to-the-electromagnetic-spectrum-and-spectroscopy/. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ U. A. Bakshi, A. P. Godse (2009). Basic Electronics Engineering. Technical Publications. pp. 8–10. ISBN 9788184315806. http://books.google.com/books?id=n0RMHUQUUY4C. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- ^ What is Light? – UC Davis lecture slides

- ^ Glenn Elert. "The Electromagnetic Spectrum, The Physics Hypertextbook". Hypertextbook.com. http://hypertextbook.com/physics/electricity/em-spectrum/. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ "Definition of frequency bands on". Vlf.it. http://www.vlf.it/frequency/bands.html. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ Mohr, Peter J.; Taylor, Barry N.; Newell, David B. (2008). "CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2006". Rev. Mod. Phys. 80: 633–730. Bibcode 2008RvMP...80..633M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.633. http://physics.nist.gov/cuu/Constants/codata.pdf. Direct link to value.

- ^ J. J. Condon and S. M. Ransom. "Essential Radio Astronomy: Pulsar Properties". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. http://www.cv.nrao.edu/course/astr534/Pulsars.html. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ A. A. Abdo et al. (2007). "Discovery of TeV Gamma-Ray Emission from the Cygnus Region of the Galaxy". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 658: L33. arXiv:astro-ph/0611691. Bibcode 2007ApJ...658L..33A. doi:10.1086/513696.

- ^ Corrections to muonic X-rays and a possible proton halo slac-pub-0335 (1967)

- ^ "Hyperphysics (see Gamma-Rays". Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/ems3.html#c5. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ "Advanced weapon systems using lethal Short-pulse terahertz radiation from high-intensity-laser-produced plasmas". India Daily. March 6, 2005. http://www.indiadaily.com/editorial/1803.asp. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

External links

- UnwantedEmissions.com (U.S. radio spectrum allocations resource)

- Australian Radiofrequency Spectrum Allocations Chart (from Australian Communications and Media Authority)

- Canadian Table of Frequency Allocations (from Industry Canada)

- U.S. Frequency Allocation Chart — Covering the range 3 kHz to 300 GHz (from Department of Commerce)

- UK frequency allocation table (from Ofcom, which inherited the Radiocommunications Agency's duties, pdf format)

- Flash EM Spectrum Presentation / Tool – Very complete and customizable.

- How to render the color spectrum / Code – Only approximately right.

- Poster "Electromagnetic Radiation Spectrum" (992 kB)

|

|||||||||||||||||